A small Ghost Goby Pleurosicya living commensally on the mantle of a giant clam (above).

Reef animals lacking symbiotic algae rely on trapping plankton from the surrounding water to satisfy their nutritional needs.  This "wall of mouths" quickly depletes the available food unless strong currents constantly bring in fresh supplies of plankton. These filter feeding animals are often more brightly coloured than symbiotic corals. |

|

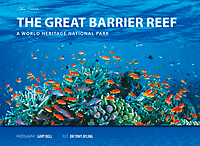

The Great Barrier Reef is an immense entity and a world renowned phenomenon. Each year, over two million visitors from around the world spend time exploring the Australian icon, marvelling at the beauty and diversity of our planet’s largest natural ecosystem. Please visit our page with links to Great Barrier Reef Photos.

| The Great Barrier Reef book - A World Heritage National Park

Photography: Leading Australian Underwater Photographer, Gary Bell

Text: Dr Tony Ayling. |

|

The official World Heritage Area Encompasses 345,400 square kilometres and stretches a distance of 2300 kilometres from the top of Cape York to Bundaberg in the south of Queensland – an area larger than Great Britain and Ireland combined. In its entirety the reef spans almost 15 degrees of latitude, one sixth of the distance from the equator to the South Pole. A modern container ship steaming at a constant speed of 18 knots takes three days and nights to traverse the inshore shipping lane that spans the length of this natural wonder – the same time it would take the ship to steam from Sydney to New Zealand ! These statistics are staggering but, as any visitor to the Great Barrier Reef will attest, the sheer other-worldliness of their mighty organism imparts an experience so much more inspiring than the magnitude of its numerical data.

Despite being known as the world’s largest coral reef, the Great Barrier Reef is not a single, continuous structure. It comprises about 1200 large offshore reefs (ranging from a kilometre to over 30 kilometres in length), as well as 1700 or so smaller patch reefs and inshore fringing reefs. Until relatively recently this vast mosaic remained mostly unknown and unexplored, save for the local knowledge garnered by a few hardy and intrepid fishermen. Although the inshore shipping channel has been thoroughly surveyed for many years, large areas of the Great Barrier Reef were not mapped or charted until late 1982 when the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority released a set of maps generated from aerial photos and satellite imagery. Many individual reefs still remain unnamed, but every reef now has its own identifying number.

A school of Fairy Basslets aggregate together over coral. Schooling is a survival strategy employed by many fish species to avoid predation. Many eyes enhance the school's ability to detect predators, while weight of numbers affords individual fish better odds against being eaten (top right).  each of the 2500 or so reefs that make up the Great Barrier Reef has been built up by stony corals. As each coral colony grows and dies it contributes to the structure of the reefs as we see them today. |

|

The human history of the Great Barrier Reef extends back to the first reef- and island-hopping Aborigines who entered the country via Torres Strait . With simple canoes and rafts they explored the many islands and cays of the Great Barrier Reef , feeding off its then untouched bounty. Although they relished the meat of turtles and dugong and gathered turtle eggs from the seaside nests, the touch of Aborigines on the reef was light compared to the impact of European colonists. White entrepreneurs and settlers in small, well-built boats combed the dangerous waters of the reef, fishing and collecting all that could be sold or used. Coral for converting to live; beche-de-mer for drying and selling to the Chinese; oysters for their valuable shells and the bonanza of rare pearls; trochus shells for mother-of-pearl; and fish for drying and salting – all were gleaned from the reef in harvesting practices that resulted in much loss of life and vessel. Exploitation slowed once the numbers of valuable species dropped to uneconomic levels, but fishing and trawling operations with increasingly sophisticated vessels continued to harvest the entire reef until the creation of the marine park in the late 20th century.

In the early 1970’s there was increasing concern that the Great Barrier Reef was being considered for oil exploration and drilling, was heavily overfished by an increasing fishing and trawling fleet, and was threatened by rapidly growing levels of coastal development and island and offshore tourism ventures. After commissioning a number of studies, the federal government reacted to public concern by passing a special act of parliament to establish the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). This body was to oversee the creation of management of a marine park that encompassed the entire Great Barrier Reef and surrounding seas. The idea behind the marine park was not to completely protect the whole area, as its usually the case for terrestrial national parks, but to manage the region in a sustainable way that would allow existing user groups to continue reasonable activities within the marine park.

The first task of GBRMPA was to campaign for World Heritage listing for the Great Barrier Reef . UNESCO conferred this privileged status in October 1981. Over the next six years the Great Barrier Reef was mapped in detail and divided into management sections that could be zoned to control their use. As zoning plans were progressively applied to each reef section, a few reefs became totally protected “no-go” preservation zones and another 5% of reefs became “no-take” marine national park zones where fishing and collecting were forbidden. Trawling and commercial fishing were still permitted over much of the marine park, and tourist and recreational users could still visit most reefs. In July 2004 a revised zoning plan increased the no-take area within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park – one-third of the total region is now off limits to fishermen and collectors. This sustainable zoning plan ensures the long-term preservation of the most significant reef habitats within the marine park.

GBRMPA and other government bodies have been encouraging research on the Great Barrier Reef for the past 30 years and scientists and other interested individuals have made important breakthroughs in understanding the complexity of the coral reef ecosystem. Coupled with the scientific study is media attention, which often focuses on the health of the reef and perceived threats t its viability. Consequently, we know have a better knowledge of the reef than we ever had in the past. Although we have coma a long way in this process over the last three decades, it is both fascinating and humbling to realise that we have still barely scratched the surface of the vast mystery that is the Great Barrier Reef .

Plankton feeding fishes on a coral outcrop, including Orange Basslets Anthias cf. cheiropilos and Blackaxil Pullers Chromis atripectoralis (top left) Most stony corals are attached to the bottom and are made up of many separate small polyps - each with a mouth and a ring of stinging tentacles that trap plankton animals from the water. |

|

Text: Tony Ayling

Source: excerpt from The Great Barrier Reef – A World Heritage National Park

Photography: Gary Bell

More Great Barrier Reef photos

| LIKE Gary Bell's Facebook page to join him on his photographic journey -

|

|